- Sections :

- More

Bissell Buzz - August 20, 2025

Bissell Buzz

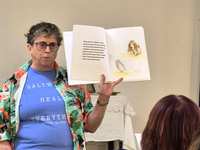

Recently, at the book signing of Bob Willis’ book “The Last Buffalo in Kansas” held in the Kirwin Library, he reminisced how different the landscape looked when his grandfather came to Kirwin. He mentioned how different the crops are now with the irrigation systems that are used. He amongst other also spoke about the end of the “horse era”.

For centuries, horses were at the center of human life. They pulled ploughs through soil, carried goods to the market, powered armies across continents and carried people to their destinations in buggies, carriages and wagons. Yes, virtually every household had a horse or two, or even more. But by the early 20th century, the world was on the cusp of transportation.

It started with the railroads and the steam engines late in the 19th century, but it was Henry Ford’s introduction of the Model T Ford in 1908 and his pioneering use of mass production, that started to tip the balance. The automobile was not a novelty reserved for the wealthy, but became a practical and affordable alternative mode of transportation for the middle-class and businesses. They started appearing in growing numbers on the streets after 1910 and by the 1920’s, they had largely replaced horse drawn transport.

The horse’s decline was not limited to the cities. Also, on farms, where horses and mules powered agriculture pulling plows and wagons across the fields, the change was imminent. As tractors became more reliable and efficient, particularly after World War I, they began to displace horse labor. By the 1930’s, mechanized farming had transformed American agriculture, reducing the need for millions of draft animals.

As the role of the horse was fading, it not only brought about a technological shift, it also was a cultural shift. The horse had been a symbol of power, speed and prestige. Entire industries like blacksmithing, carriage-making and harness production, were built around the horse. As cars, trucks and tractors became dominant, these crafts declined too. The horse retreated from everyday life and became more associated with sport, leisure and rural traditions than with work or transportation. Today, many ranchers resort to the use of modern ATV and UTV’s when rounding up their cattle to either handle or move them. Fortunately, there still are a few real cowboys around, that round up their cattle on horseback and rope the young animals from the saddle for branding and other handling.

The horse however, in a way has been immortalized by using horsepower as a unit of measurement, referring to the sustained output of an engine. This unit of measure was developed in the later 18th century by James Watt (after whom the watt is named), as a way to demonstrate the power of steam engines. Logic would suggest that the power of one horse should equal one horsepower, but the measurement is meant to represent a horse’s continuous output over a full workday, not what horses are capable of in short bursts of extreme effort.

Watt calculated that in an average day’s work, a horse could turn a 24-foot mill wheel roughly 2.5 times per minute. This amount of energy worked out to 33,000 foot-pounds (approximately 746 watts) per minute, which Watt deemed a new unit of measurement called horsepower.

In 1993, biologists R.D. Stevenson and R.J. Wassersug used data from the 1925 Iowa State Fair horse-pulling contest to calculate the maximum output of a horse over a short period of time, ultimately finding that one horse can exert up to 14.9 horsepower. Humans, by comparison, have a maximum output of slightly more than a single horsepower.

It's sometimes suggested that Watt deliberately underestimated the power output of a horse to help promote his new steam engine. But Watt’s calculations weren’t technically incorrect; he just presented them in such a way to make his engines seem more attractive. He emphasized sustainable rather than peak performance, underlining the fact that, unlike horses, his engines could work all day long without tiring. It’s because of this that a single horse can actually be capable of nearly 15 horsepower — at least over short periods of time.

Even though our 2025 season is drawing to a close, we have a few events lined up. A brief list of these are as follows:

Girl Scout Day Camp – September 13 – only for Girl Scouts

Night at the Museum – September 28

Ellis Trail to Nicodemus Movie – October 5

Untold Stories of Indian Battles in NW KS – October 18 (At Huck Boyd Center)

Chili Cookoff – November 2

Until the end of August, our hours remain:

Tuesday to Friday 9am to 4pm

Saturdays 9am to 2pm

Ruby Wiehman – Curator